Transportation of oil by water was the indirect result of the first oil well. Mineral oil had been known to exist below the surface of the earth for quite some time. There are indications that the Chinese obtained small quantities from shallow mines several thousand years ago, but the small quantities obtained by them and people inhabiting the Middle East could never have justified the time and energy needed in developing it as a fuel for heating, lighting, and the multitude of other purposes which man has found for oil in the present highly Industrial Age. The first oil well was sunk in Pennsylvania in June 1859, and it was brought in at a depth of some seventy feet, on August 27th of the same year.

The Elizabeth Watts is generally credited with being the first ship to carry a full cargo of oil across the Atlantic. She commenced her career in 1861. Several factors tended to retard the development of the early tanker, not the least of these was the attitude of owners and crews of the numerous wooden sailing ships of that period. Not without cause they regarded oil as a dangerous cargo. Leakage from barrels in the holds resulted in the spaces below deck becoming permeated with dangerous gas, which slowly made its way into the living accommodation, this in turn meant disaster or extreme discomfort as all lamps and cooking fires had to be extinguished.

The use of the iron hull to some extent offset these difficulties, and several sailing ships were built and converted for this trade. Several were fitted with specially built tanks for the carriage of oil. The future of the oil trade was then thought to lie in the large iron hulled sailing ship, fitted with iron tanks and equipped with hand pumps for the rapid and safe discharge of cargo. The idea of using a steamer for such cargo was as yet unthinkable, due to the danger of vapour reaching the coal fires in the machinery spaces.

As the industry developed, so did the early tanker. In 1878, the first ship to use the hull or skin as a container for oil was built. This vessel was called the Zoroaster, and her building marked a major step in the development of the modem tanker. To the bolder minded, the advantages of a steam-powered tanker became apparent, apart from the question of propulsion, steam powered pumps were an added advantage. To control the flow of liquid when the vessel was rolling in a seaway, and to avoid large areas of free surface, the tanks were provided with trunk-ways, which considerably reduced the area at the top of the tank. Vessels, however, were often far short of their marks when loading light products, later types began to incorporate the “summer tank” which was housed on the trunk deck and was generally filled by means of a drop valve from the main tank below.

Towards the middle of the 1920’s, the twin bulkhead ship made its appearance, and slowly but surely the advantages of the new design made itself felt, and the centre line bulkhead type began to be replaced in all but a few special types and coasters, where size made the twin bulkheads impracticable.

Welding was used in ship construction for a considerable period before World War II. However, where hull construction was concerned, welding was always viewed with grave suspicion, but like all new methods, material and techniques improved, and during World War II whole ships were constructed on this basis. The advantage of the welded hull is fairly obvious. All the plates are welded in a straight line, and there are no plate landings to restrict the flow of water along the hull as the vessel is propelled through the water. In addition to this, rivets have a tendency to work, leaks from this source are quite frequent both in the hull and in the bulkheads separating the cargo tanks. Welding has more or less eliminated leakage of this nature.

T-2 tanker from 2nd world war

In the last ten to fifteen years, a great deal has been learnt about the use of metal in all types of construction. Research into metal fatigue and wastage as well as the use of coatings to prevent this, has helped considerably to simplify some of the problems encountered when carrying highly corrosive hydrocarbon liquids. Large-scale models in ship model basins have assisted the ship designer to examine stress problems and to simplify the design and layout of large tankers, thus reducing the cost of construction.

Apart from the layout of the cargo compartments and pumping systems, there have been significant changes in other directions, e.g. power operated valves and remote control are becoming increasingly common. Properly used and maintained, such improvements show an economic return by reducing manpower requirements and eliminating human error from a complex operation where expensive equipment can be seriously damaged.

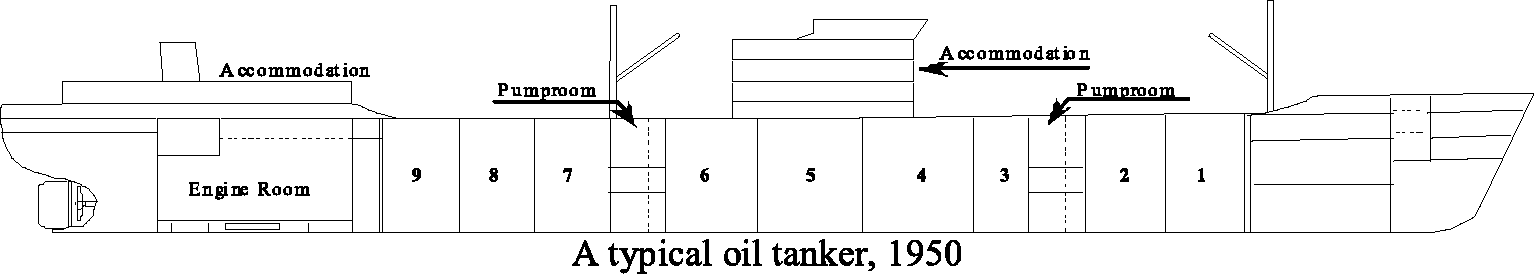

It would not be wise to neglect other areas where changes are taking place. Nearly all the new ships have no amidship house. The bridge and living accommodation are located aft. Safety and economics have been the main reason for this change and the arguments of Masters and Pilots who have opposed it on navigational and ship handling grounds can find little support today.

My recently-published biography of Daniel Keith Ludwig entitled ‘Capitalism in the Epic Sense’ tells in detail the history of his initiatives in shipping oil, rising to become known as ‘The Father of the Supertanker’. Ludwig also became, over several years, the richest man in the world, and bequeathed his entire fortune to cancer research, carried out by the Ludwig Institutes that still bear his name today. .